I think of the 45 years I worked with policy issues and programs in the healthcare arena between 1940 and 1985 and, most specifically Medicare – Medicaid. The country's infrastructure has changed over the course of the past few years with some changes that are still unclear to date. Our lessons have evolved over the past decade or so.

I don't see the 1965 bill as an improvement or failure of a particular government or as an expansion of that role. The second problem arose out of the strong opposition of Senator Pat M. McNamara (D., Michigan) to any deductible on hospital insurance.

My current comments are historical and it is necessary that I spent fifteen years assisting Congress1 in developing the basic structure which became known under Medicare and Medicaid.

I stayed in the same office for 312 years, 1965-1968, assisting with the first decisions concerning the development, management and operation of both programs. Understandably, it is difficult for me and my associates to understand the importance of these programs.

I will review and examine specific provisions for Medicare in a prior article and for the purposes I participated in. I have chosen the provisions or policy provisions of these two laws that have remained ambiguous if not misinterpreted. The legislative development in this regard has not impacted the existing literature in the past or has been discussed elsewhere, e.g. Harris et al, 1965.

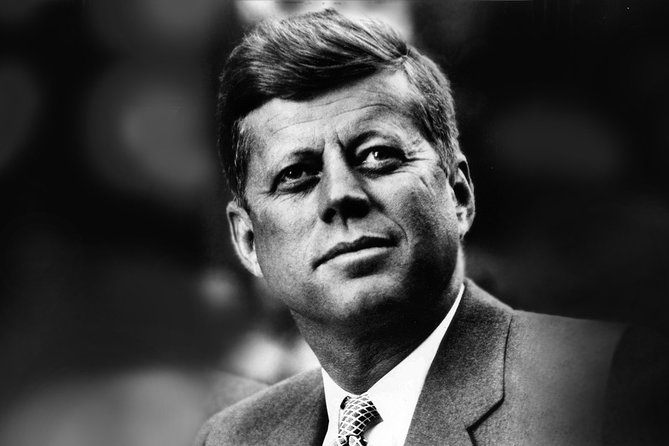

Healthcare Financing Reviews Center for Medical Assistance. Wilbur A. Cohen. Additional article information. President John F. Kennedy delivered the following speech before the National Council of Senior Citizens. Edward Annis rebuts President Kennedy 's Medicare push at Madison Square Garden, where the president had spoken two nights earlier.

The main pressure on the implementation of Medicaid began to develop in 1942, after Rhode Island opted to use the existing social security funds to provide direct payments to providers of health care. The government reportedly argued that the law didn't allow such restrictions.

This led some Social Security Board members to propose a proposal to modify the statute specifically for this “vendor pay”. A federal government-sponsored comprehensive government benefit program would be created which could provide for “medical assistance”.

Cohen and Ball (1965) and Cohen and Peerboom (1969) offer a comprehensive legislative history for the 1965 act. Some pamplets, headlines or argumentations are mentioned in "Campedon" (1984) and Harris (1965). Despite strong public support, the bill was defeated in 1962, due in part to opposition by powerful forces, including the American Medical Association.

A detailed analysis of this political battle is presented in 12 oral histories published in the library at the Columbia University Library. Corning, 1968. 3I was a contributing member in writing the Wagner-Dingell Comprehensive National Health Insurance Act of 1943 and the TruMan Health Statement of 1945.

Wilbur J. Mills was an ardent advocate of contributions to social protection systems throughout his lifetime. He was both an economic conservative, and an observant and prudent Democrat. Before 1963, he was not an endorser for Medicare.

However, a careful expression of his opposition is a good way to allow for room to adapt to new opportunities. Despite having doubt in his mind that this could be done via the social security system, he would commit himself to opposition, notably to King Anderson's proposal.

Hospitals were a topic of employee debate in some way since 1942 when the first federal nationwide insurance bill came to Congress. Several different variations in this legislation helped identify administrative issues and progressively decide how to handle them.

In the early 1960s a change in disability insurance legislation greatly assisted in the development and maintenance of medical certification policies and forms, building relationships with physician and hospital personnel.

Wilbur J. Cohen was the first professor of public administration at Texas A & T since 1980. His work has been cited as a major contribution to a national task force to address health and social security. But reformers regarded Kerr-Mills as inadequate, given the rising number of elderly and the rising cost of hospital care.

Between 1960 and 1968, he served as Under Secretary for Health, Education and Welfare and was the only person with these roles. In his early career he had a leading part in creating the Medicare and Medicaid program, which led to pilots and initial implementations by Congress.

It has not been debated or opposed in the periods 1961 – 65 since the Social Security Act based the social security provision of the Social Security Act. It was adopted by the Congress and the suppliers. No one reviewed this bill during the legislative process. Nobody considered it as an indicator of inflation.

In recognition of Anderson's efforts, President Johnson invited him to attend the Medicare signing ceremony in Independence, Missouri, with former president Harry Truman.

Section 1903 and 1965 Medicaid legislation provides that the Secretary shall not be required to pay any state under the previous provisions of these sections until the State has proven that a satisfactory showing that a reasonable effort is being made to broaden the scope of care and services provided.

A federal government website managed and paid for by the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Finally, on July 30, 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed Medicare into law. Both Rep. Anderson and President Harry Truman, who had also proposed such a program twenty years earlier, were present at the signing, which took place at the Truman Library in Independence, Missouri. Mills, Chairman of the House Committee on Ways and Means, to report out the Medicare bill.

Though public opinion polls suggested strong support for the bill, Anderson faced powerful opponents, including the House Ways and Means chairman, the American Medical Association, and Senate Finance Committee chairman Harry Byrd of Virginia.

Section 1801 of the Medicare legislation is interpreted to mean that no federal officer or employee has the right to exercise any supervision or control on the practice of medicine or on the way that medical assistance is provided.

While Obama crosses his fingers and waits for healthcare.gov to flicker to life, he can at least comfort himself knowing that he has already done more to reform the health care system than JFK, a president with a vigorous reputation and vibrant legacy.